Kata Containers: When Containers and Virtual Machines Make a Baby

In March this year, we celebrated the 10-year anniversary of Docker, a technology that revolutionized the way we build and deploy applications. The adoption was explosive—so explosive that it’s extremely difficult to find a developer today who isn’t using containerization technology in some capacity.

The next evolution of containerization technology, Kata Containers, is still relatively unknown. To fully grasp the significance of its emergence, it’s essential to take a journey back to the roots of virtualization technology.

Xen Hypervisor & Hardware-Assisted Virtualization

In simple terms, virtualization allows a single physical computer to be divided into multiple virtual computers. This magic is achieved through a piece of software known as the hypervisor.

While the concept of virtualization dates to the late 1960s, significant advancements were made in the mid-2000s. In 2005/2006, Intel and AMD introduced hardware-assisted virtualization with VT-x and AMD-V technologies for the x86 architecture. This enabled virtual machines (VMs) to operate with minimal performance overhead. That same year, the Xen hypervisor incorporated VT-x and AMD-V, setting the stage for the rapid growth of public cloud platforms like AWS, GCP, Azure, and OCI.

As businesses increasingly adopted cloud services, the need for heightened security became paramount, especially when different clients shared the same physical hardware for their VMs. Hypervisors leverage hardware capabilities to ensure distinct separation between VMs. This means that even if one client’s VM experiences a crash or failure, others remain unaffected.

Going a step further, AMD introduced Secure Encrypted Virtualization (SEV) technology in 2017, enhancing VM isolation. With SEV, not only is data protected from other VMs, but it also introduces a “zero-trust” approach towards the hypervisor itself, ensuring that even the hypervisor cannot access encrypted VM data. This offers an added layer of protection in a shared-resource environment.

The Emergence of Containers

Virtual machines streamlined application deployment by abstracting the underlying hardware. However, they introduced new challenges. For instance, there was still the responsibility of maintaining the operating system (OS) on which the application ran. This involved configuring, updating, and patching security vulnerabilities. Furthermore, installing and configuring all the application’s dependencies remained a tedious task.

Containerization emerged as a solution to these challenges. Containers package the application together with its environment, dependencies, and configurations, ensuring consistency across deployments.

Recognizing the need to simplify OS maintenance further, AWS launched Fargate in 2017. With Fargate, developers can run containers on the cloud without the overhead of OS management. As the popularity of containerized applications surged, orchestrating these containers at scale became a challenge. This was effectively addressed by technologies like Kubernetes, which automate the deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications.

Building on the Foundations

Having understood the intricate evolution of hardware capabilities over four decades, we appreciate how instrumental these advancements were in enhancing both performance and security for virtual machines. These developments have made it feasible to run multiple virtual machines on a single physical host without significant performance overhead while also maintaining strong isolation between them.

However, when it comes to containers, a different approach is taken. Unlike virtual machines, which rely heavily on these hardware-based virtualization features, containers don’t create whole separate virtualized hardware environments. Instead, they function within the same OS kernel and rely on built-in features of that kernel for their isolation.

At the heart of container isolation is a mechanism called namespaces. Introduced in the Linux kernel, namespaces effectively provide isolated views of system resources to processes. There are several types of namespaces in Linux, each responsible for isolating a particular set of system resources. For example:

- PID namespaces ensure that processes in different containers have separate process ID spaces, preventing them from seeing or signaling processes in other containers.

- Network namespaces give each container its own network stack, ensuring they can have their own private IP addresses and port numbers.

- Mount namespaces allow containers to have their own distinct set of mounted file systems.

And so on, for user, UTS, cgroup, and IPC namespaces.

The beauty of namespaces is their ability to provide a lightweight, efficient, and rapid isolation mechanism. This makes it possible for containers to start almost instantaneously and use minimal overhead, all while operating in isolated environments.

However, it’s essential to understand that while namespaces provide a degree of isolation, they don’t offer the same robust boundary that a virtual machine does with its separate kernel and often hardware-assisted barriers.

Kata Containers is Born

Building on the foundation of virtual machines and containers, Kata Containers emerged as a solution that seamlessly fuses the strengths of both worlds.

Traditional containers, with their reliance on kernel namespaces, bring unparalleled agility and efficiency. They can be spun up in fractions of a second and have minimal overhead, making them perfect for dynamic, scalable environments. On the other hand, virtual machines, backed by decades of hardware innovation, offer a more robust isolation boundary, giving a heightened sense of security, especially in multi-tenant environments.

Kata Containers seeks to bridge the gap between these two paradigms. At its core, Kata Containers provides a container runtime that integrates with popular container platforms like Kubernetes. But instead of relying solely on the kernel’s namespace for isolation, Kata Containers launches each container inside its lightweight virtual machine.

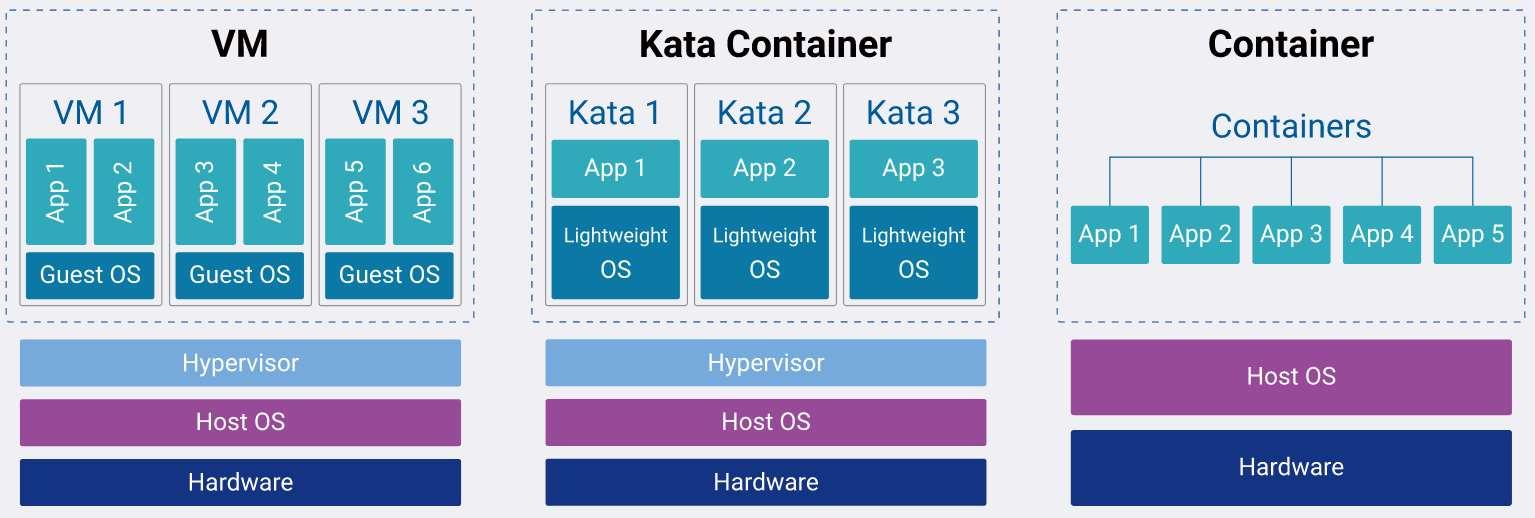

The below diagram demonstrates the difference between VM, Kata Containers, and conventional containers.

Kata Containers in Action

Previously, we discussed AWS’s Fargate service, which allows users to run containers without the need to manage the underlying operating system. This approach streamlines operations, but it also introduces certain security challenges.

To address these security concerns, AWS employs a strategy reminiscent of Kata Containers. Instead of running your container directly on the shared OS kernel, AWS encapsulates each container within a lightweight virtual machine. This extra layer offers enhanced security by providing a robust isolation barrier akin to that of a fully-fledged VM.

This technique is made feasible by the Firecracker project, a lightweight virtual machine monitor (VMM) designed for high-density container workloads. Kata Containers supports Firecracker as one of its runtimes.

Another notable application of this technology can be seen in Azure’s adoption of “Confidential Containers”. As businesses increasingly look towards the cloud to handle sensitive data and critical operations, ensuring the confidentiality and integrity of this data becomes paramount. Traditional containers, while agile and efficient, might not always meet the rigorous security requirements—especially when handling sensitive data in shared or multi-tenant environments.

Enter Azure’s Confidential Containers. These containers are designed to run on Azure Confidential Computing infrastructure. By leveraging hardware-based Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs), Confidential Containers ensure that data remains encrypted not only at rest and in transit, but also while it’s in use. This means that even if the underlying infrastructure or OS kernel were compromised, the data within the Confidential Container remains secure.

Until now, Kata Containers might seem to primarily address the needs of large public cloud operators. However, I will now demonstrate how they can be effectively utilized in your CI/CD pipeline. Imagine you are responsible for the development and maintenance of a kernel module, such as a kernel mode sensor—a common tool in the cybersecurity industry—which does not interact directly with hardware. The challenge here is to test your module across a wide range of kernel versions and Linux distributions. Kata Containers can be a solution to this problem, as they allow the launching of containers with various kernel versions in mere seconds. This enables you to test the functionality of your kernel module across all necessary versions using significantly fewer resources than what traditional virtual machines would require.

Another valuable application of Kata Containers is their use in forensic checkpoint-restoration for containers. While securing containerized applications, there are moments when a particular containerized workload warrants deeper inspection. In such cases, it’s possible to capture the container’s current state as a snapshot and then restore it inside a Kata Container. This approach allows for in-depth forensic analysis without endangering the entire node, a task that would otherwise be challenging given real-world time and resource constraints.

Conclusion

Kata Containers adeptly combine the efficiency of containers with the security of virtual machines, catering to a diverse range of cloud computing needs. This makes them a practical choice for scenarios like secure multi-tenant environments, resource-efficient CI/CD pipelines, and the unique demands of edge computing and IoT. Their versatility and balance between performance and security position Kata Containers as a useful tool in the evolving landscape of cloud technology and IT.